- Home

- Wright, Callie

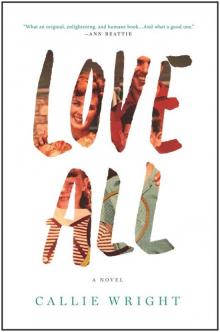

Love All: A Novel

Love All: A Novel Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

TO MY MOM AND DAD

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A tremendous thank-you to my agent, Amy Williams, for her matchless enthusiasm and ardent support, and to my editor, Sarah Bowlin, for her unerring guidance and indispensible insight beginning to end. To everyone at Holt who helped usher this novel into the world, I am genuinely grateful.

Thank you, too, to my colleagues at Vanity Fair with whom I have worked these last nine years, especially John Banta and the entire Research Department. If writing a novel is a solitary endeavor, I never felt it.

I have been fortunate to have generous and gifted teachers over the years: Rick Moody, Bertha Rogers, and Helen Schulman, whose encouragement from the time I was fifteen years old has sustained me; Robert Stone, who took me under his wing at Yale; and Ann Beattie, John Casey, Deborah Eisenberg, and Christopher Tilghman at the University of Virginia Creative Writing Program, who supported me then and now—thank you.

For their thoughtful and loving feedback—friends whose careful consideration has helped shape this novel in the best ways—my deepest gratitude to Taylor Antrim, Brian Berry, Kate Berry, Luca Borghese, Alison Forbes, Marnie Hanel, Laura Haverland, Jenny Hollowell, Cassie Marlantes Rahm, Jebediah Reed, Makeba Seargeant, Doug Stumpf, and Lilly Tuttle. For a formative supply of grilled cheese sandwiches and Cokes with a cherry in them, thank you to Bebe and Papa. A very special thank-you to Eleanor Henderson and Mary Beth Keane for their sage advice, and to Molly Cooper, who has read this novel as many times as I have.

I owe a debt of gratitude to everyone in Cooperstown, my oldest friends, who share my memories of the village. To those of you who spoke to me about life in Cooperstown in the 1960s, I could not have put Nonz and Poppy there without your help. To Nick Alicino, tennis coach, English teacher, and friend, you live on in our stories. And to Jamie Bordley and Peter Townsend—everywhere I looked, you were there.

Finally, I could not have written this book without the people who cheer me on every day—thank you to my brother, Stuart, my biggest fan, for always being on my team; to Jenny, Cooper, and Grayson, for making everything fun; to my beloved Gigi, for her faith in me and for her friendship; and to my parents, Peggy and Tom, for their endless love and for moving us to Cooperstown.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

About the Author

Copyright

1994

PROLOGUE

In a bizarre coda to parenthood—played out at the advanced age of eighty-six—Bob Cole had been recast in the role of needy newborn, and just as Joanie had for their daughter forty-odd years ago, now his wife got up with him, trailing Bob to the bathroom and standing sleepily outside the door to chat. At midnight, she was there describing the spring blooms she anticipated any day now: Hadn’t he noticed the crocuses already leafing, marking the place where their violet flowers would soon skirt the stems of the tulips? It was possible that the soil bed didn’t get quite enough sunlight, she admitted, which likely meant that not all the bulbs would come up, but still it would be something new this year, not the same old daffodil mix they’d always done.

Bob had never planted a flower in his life, but Joanie would have him believe he was as integral to the goings-on of their household as he had been when he’d run his own insurance agency, paid the bills, and treated his wife and daughter to weeklong summer vacations at a furnished cabin on the lake. His revisionist wife: if Joanie still thought of him as that six-foot-tall man with a full head of hair, she seemed to have forgotten his erstwhile propensity for a few pastimes less wholesome than gardening.

At four A.M., Bob again slid out from under the covers and this time Joanie didn’t stir and the bathroom light didn’t rouse her, and Bob was pleased to think that she was so deeply asleep. How tired she must be, how completely exhausted from all this tending. Twelve years her senior and their age difference had never felt more pronounced.

From the window above the toilet Bob could see down to the backyard, where Joanie’s flower bed was cast in gibbous moonlight. The crocus leaves were jutting through the snow, just as Joanie had described, mapping a pattern so complex that Bob wondered if his wife had plotted it out on paper before laying spade to soil. When had she found the time? Soon the sky would shade salmon pink and they’d begin their day with coffee and orange juice, eggs and toast, and a grapefruit split between them. After breakfast, Bob would read the paper in his recliner by the kitchen while Joanie did the dishes; late morning, she’d heat soup for their lunch while he napped in his chair.

In the early afternoon they’d go for a drive up the scenic lake road or through the winding farmlands of Cherry Valley, routes without destinations, the luxury of being old. Joanie piloted Bob’s Buick, touring them through the countryside they’d both grown up in: past six-mile point, where Miller’s Pioneer Restaurant had been their Sunday-night destination when they were first married, then cresting Mount Wellington, with its bird’s-eye view of the lake. In the winter Bob could see straight down to the swimming area of Camp Chenango, where he’d been a vanguard sailor as a young boy; in the summer the seasonal Springfield Hill Road carried them over to Route 33, and they drove alongside muddy farm fields lined with plastic sheets holding down feed or bales of hay.

In the late afternoons their granddaughter, Julia, occasionally stopped by with her friends, and these visits were plainly the highlight of Joanie’s week. She plied the kids with molasses cookies and lemonade, while Julia, Sam, and Carl spoke in a private language they found so funny, it had the power to drop even the towering Sam to the floor. Had Bob ever been so young? Not that he could remember. Certainly if he’d managed to bring home a girl at the age of fifteen he wouldn’t have been playing board games with her in the sitting room.

When the diuretics had finally done the work for his heart, Bob felt his way back to bed and soon dropped into the seal-clubbed slumber of children, that impenetrable state in which his heart could quietly rest while he slipped into a dream. This time he made his way to the country club, to the great lawn beneath the brightly lit clubhouse, where a horn section was beginning to chop out the first notes of “Rug Cutter’s Swing.”

From the end of the dock, he heard a soft splash followed by a man shouting, “Now look what you’ve done,” then the reverberations of the diving board. A silhouetted set of tuxedo tails beat the air like wings.

“Should we join them?” a woman asked, and Bob looked left and saw a head of cropped blond hair, a face he’d nearly forgotten, her cheek shadowed by the collar of his own suit jacket draped over shoulders that were otherwise bare.

Bob jerked awake to find daylight edging the linen curtains in the bedroom and tinting the white cotton flaxen. He was not just thirsty but parched, desperate for a glass of water.

“Joanie,” he whispered.

Next to him, his wife lay supine, eyes closed, and anyone might have thought she was asleep except that she rarely slept on her back, usually on her left side, curled vigilantly toward Bob, a habit she’d developed

early in their marriage.

Bob touched her cheek, then quickly pulled his hand away. He pushed up on his elbow and lowered his good ear to her chest, but his labored breath was an amplified rasp in the otherwise silent room.

“Joanie?”

He patted her cheek—slapped her, really—then took her by the shoulders and shook her until her nightgown bunched over her clavicles and wadded at her neck. She was tangled in the sheet, the chenille bedspread, the wool blanket she insisted on right through summer, and when he tried to lift her, to force her upright, their nest of bedding tugged her down.

Bob glanced at the phone on Joanie’s nightstand—should he call Dr. Brash? 911? From his own edematous lungs, could he breathe air into hers? A vitality that had eluded him for years brought Bob up to his knees on the bed and found him pushing Joanie’s hair off her face, then placing his mouth over hers. He exhaled without count, inhaled without rhythm, and when his breath grew short, he rubbed his wife’s frail chest until he was reoxygenated, ready to start again.

And he would have gone on indefinitely—better to be dead than to be left here alone—except that he suddenly remembered Joanie had not gotten up with him the second time in the night. The realization that it had likely been hours, that his own consciousness was not inextricably linked to hers, that the moment he understood her to be gone was not in fact the moment he had lost her, slipped over him like a noose. In fifty-four years of marriage, Bob had never anticipated having to live without his wife and yet here he was already well into his first day.

Bob studied Joanie’s mouth, her jaw set, her lips pulled into a faint grimace: a look he’d been given hundreds of times but not in many years. While he had been dreaming of one in a long succession of marital betrayals, Joanie had been perpetrating her own. Not divorced but widowed—she had left him after all.

He’d have to call someone eventually, but Bob wanted no part of whatever came next. It occurred to him that this might be the last time he’d ever be alone with his wife and he wondered if the fact of her death precluded the possibility of her hearing him, should he have a few things to say.

It took him a moment to get going. He seemed to have lost his voice. He couldn’t remember how he had spoken to his wife, then he could remember—not the easy rapport of the last twenty years, but Bob talking a mile a minute to outpace the heavy silence of Joanie refusing to ask him where he’d been the night before—and he quickly opened his eyes to dispel the image of their younger, unhappier selves.

Wearily, he sank to his elbow and let his face hover above Joanie’s. He stroked her cheek with the back of his hand, then kissed her temple. He wanted her back; he tried to memorize her—wavy white hair curled behind her ears, high cheekbones, sun-spotted skin—but Bob’s memory played tricks on him.

Yesterday he’d found Joanie in the study with a photo album open on her lap, documentation of one of those long-ago family vacations at the cabin on the lake. The album’s protective cellophane bulged over each yellowed Polaroid.

“What are you looking at?” he’d asked.

She pointed to a photograph in the middle of the page: Bob and Anne standing in the shallow water near the gravelly shore. Bob’s gingham bathing trunks were damp against his muscled thighs, the cord tied in a neat bow beneath his flat stomach. Anne clung to Bob’s shoulders with exaggerated hilarity, her arms crossed around his neck, her feet wrapped around his waist, her baby-toothed grin just visible above his bright blue eyes.

“Remember the rain that summer?” asked Joanie.

But the sky in the photograph was utterly cloudless and Bob’s bathing trunks were faded, as though he’d spent every day of the vacation watching their five-year-old daughter paddling around the end of the dock.

“It looks nice,” he observed.

“That was the only sunny day.” Joanie tapped the photo. “You took Annie swimming right before we had to return the keys.”

Selective memory, Anne would call it now, and Bob thought of his grown daughter, who wouldn’t hesitate to conduct an unofficial inquest into her mother’s death and find him guilty in every way. What had happened to that little girl who’d held on to his neck for dear life? What had happened to the grandchildren who’d stood on chairs in the kitchen next to Joanie in Bob’s old dress shirts so that they could roll out dough, sprinkle flour, measure sugar by the tablespoon? Now Teddy was a senior in high school and Julia was almost driving and Bob couldn’t remember the last time one of them had spent the night. It was Joanie who had kept track of the kids’ birthday parties, concerts, awards ceremonies, sporting events. She’d organized everything, and Anne would never let him stay in this house without her, but where else could he go?

Only three days ago, Anne had invited Joanie and Bob over for an early dinner and their son-in-law had been so distracted during the meal, so jumpy—up for another bottle of wine, down for a third glass of it—that Bob had grown exhausted just watching him.

“Something’s going on with Hugh,” Joanie had commented on the drive home.

Going on.

It was the same thing she’d once said about Bob, and she’d been both right and wrong—though through it all Bob had loved his wife.

Now he laid his head next to hers and took her hands in his. They’d attended two or three funerals this year alone and yet he couldn’t come up with a single prayer, one proper snippet of grace to deliver over his wife’s body. He might’ve wished her a safe passage or told her he’d see her soon, but he ran up against an age-old failure of imagination. Still, he could appreciate a sense of calm Joanie might enjoy from having an entire day off: no breakfast to fix, no bed to make up, no old man to worry about. And there would be people she’d want to see. Her parents; her beloved grandmother, Rose; Nora Ames and Pearl Olsen, childhood friends; her sister, Ellie, killed in a car accident only months before Joanie and Bob had met; and Joanie’s high school sweetheart, Cope Ward, starting quarterback, homecoming king, the spitting image of Robert Taylor.

There were so many ways a life could go. If Cope hadn’t enlisted, melting in the Alabama sun at Fort McClellan while Bob, ten years older, settled in back home. If Bob’s crush, Josephine Gibson, hadn’t hastily married Frank Flag the night before Frank had boarded a bus bound for Kelly Field in Texas, a kid who’d never been on a plane but was eager to learn to fly. If Frank hadn’t been practicing maneuvers in the mountains of New Mexico when, a month later, a windstorm churned up under his wings, requiring an emergency landing and sending him home an injured man. If Josephine hadn’t been so loyal—she and Bob had quietly courted while Frank was away, but all that had to stop now. And if Bob hadn’t gone to the hospital to say goodbye to Josephine, he might never have seen her: that lovely young nurse tending to the white bandages that seemed to cover Frank everywhere.

“Bob,” said Josephine. “I don’t think you know my friend Joanie.”

Short chestnut hair, dark eyes, skin the color of the inside of an almond. Bob had waited for her to offer her hand but she was too busy spinning out gauze like cotton candy, so he studied her fingers, long and slightly tapered. The back of her neck formed a cleft at the nape when she leaned over with her silver shears, her pink lips pressed in concentration.

“Be good,” said Josephine, no longer a lover but a friend, already slipping into her role as Frank’s wife, while Bob, who had never been faithful to any woman, silently promised that he would.

1

Tuesday morning Hugh crept out of the house at just after six o’clock wearing a dark fleece jacket and a wool ski hat yanked low over his brow. On Beaver Street, Eric Van Heuse, Teddy’s former Biddy Basketball coach, was out collecting his newspaper, while the Erley children, three doors down, had corralled their overweight tabby on the front walk, fencing the cat with their legs and giving him a push toward their house. If Coach Eric waved, Hugh didn’t see it. He’d hunched his shoulders to the sun and trained his eyes on the ground.

Normally, Hugh happily stopped to talk

to every person he met. His wife and children’s irritants—busybody neighbors and the absence of fast food, respectively—were Hugh’s raisons d’être. He was a long-standing member of Save Our Lake Otsego and the Cooperstown Chamber of Commerce; he faithfully attended school-board and town-council meetings; the Seedlings School cosponsored soccer and Little League teams; and Hugh rode on a float in the nearby Fourth of July parade. Today, however, he was keeping a low profile.

He had been up half the night reading about factors influencing memory acquisition in young children, and for a certain boy, visual reinforcement, in the form of Hugh’s face, had to be avoided. Dressing like a cat burglar, taking a roundabout route to work, hiding in his office, and generally steering clear of Graham Pennington, age five, would be Hugh’s tactical offense against the sharpening of any fragmentary memories in the child’s mind. Two weeks had passed since the hospital-room incident, which would work to Hugh’s advantage: with any luck, Graham had already forgotten that he’d encountered his preschool principal beneath his mother’s spread legs.

Hugh unlocked the school at six thirty and was relieved to find it exactly the way he’d left it a week ago. Someone had been as careful with the rooms as he was. Lights turned off, play rugs prepped for morning play, the playground raked, and the toys put away. Everything was fresh and ready to go. Mrs. Baxter had even primed the coffeepot in the tiny teachers’ room so that all he had to do now was flip the switch to set the grounds brewing.

It had been a somber week since Hugh’s mother-in-law had unexpectedly passed, long days filled with funeral and interment plans; cleaning out and listing his in-laws’ house; and installing Bob Cole in their guest room for what looked to be a permanent stay. It was Hugh’s opinion that his father-in-law—eighty-six years old, with congestive heart failure and a walker—belonged in the Thanksgiving Home. Hugh’s wife, however, disagreed. It had been a long-standing plan for Anne’s mother to move to 59 Susquehanna when her father passed, and now Anne argued that they had to extend the same invitation to her dad. Never mind that Joanie, a spry seventy-four-year-old former nurse who baked and cleaned—a welcome addition to any household—had been positively winning in comparison to Bob. Never mind, too, that Anne herself could barely tolerate her father. It was the right thing to do, she’d persisted, and more to the point: What would people think of her if she didn’t?

Love All: A Novel

Love All: A Novel